02 Reflection on Hamja’s collective dream work zine hang out & Think in by Anna Lina Litz

Collective dream work: zine hang-out and think-in

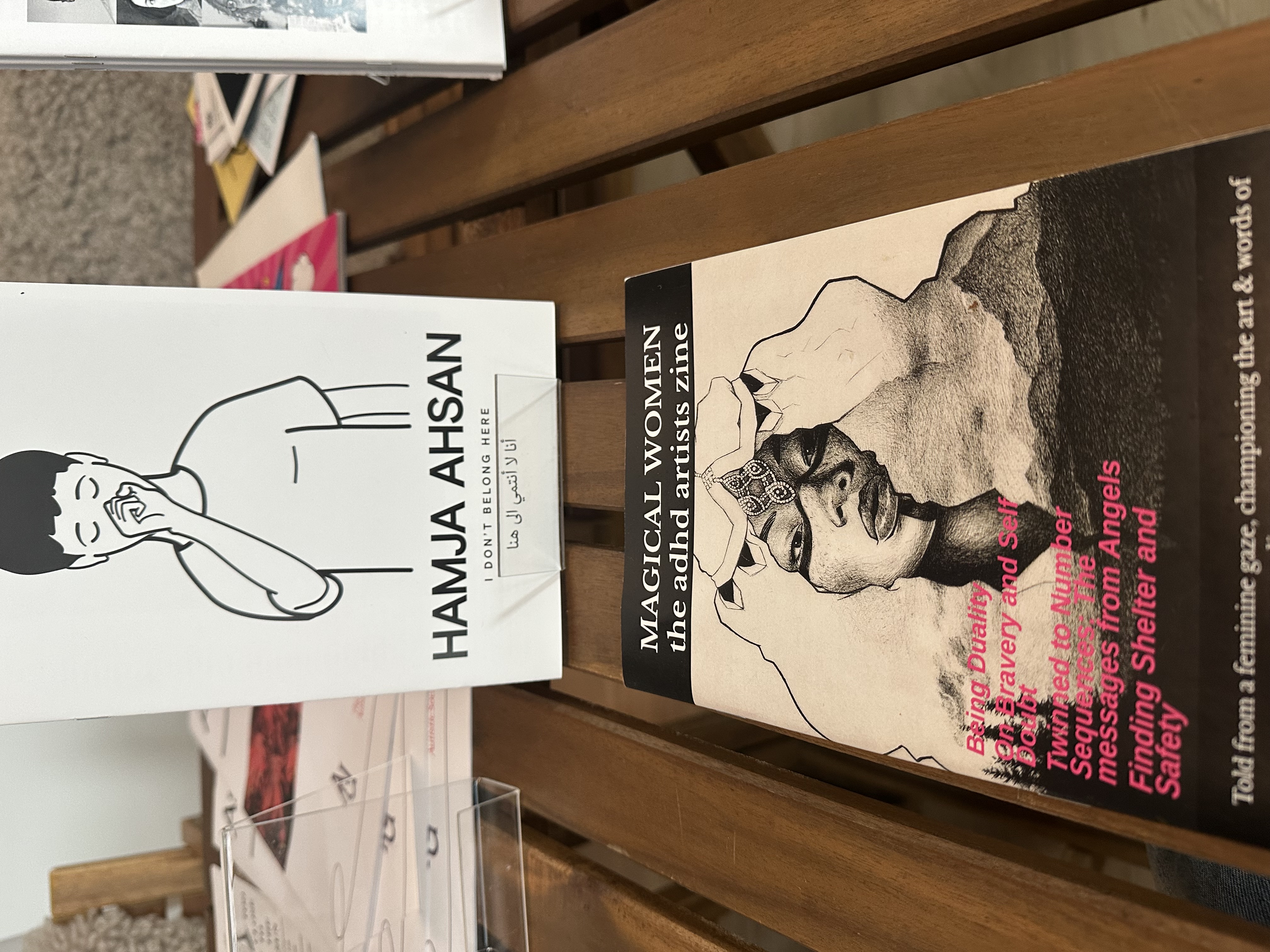

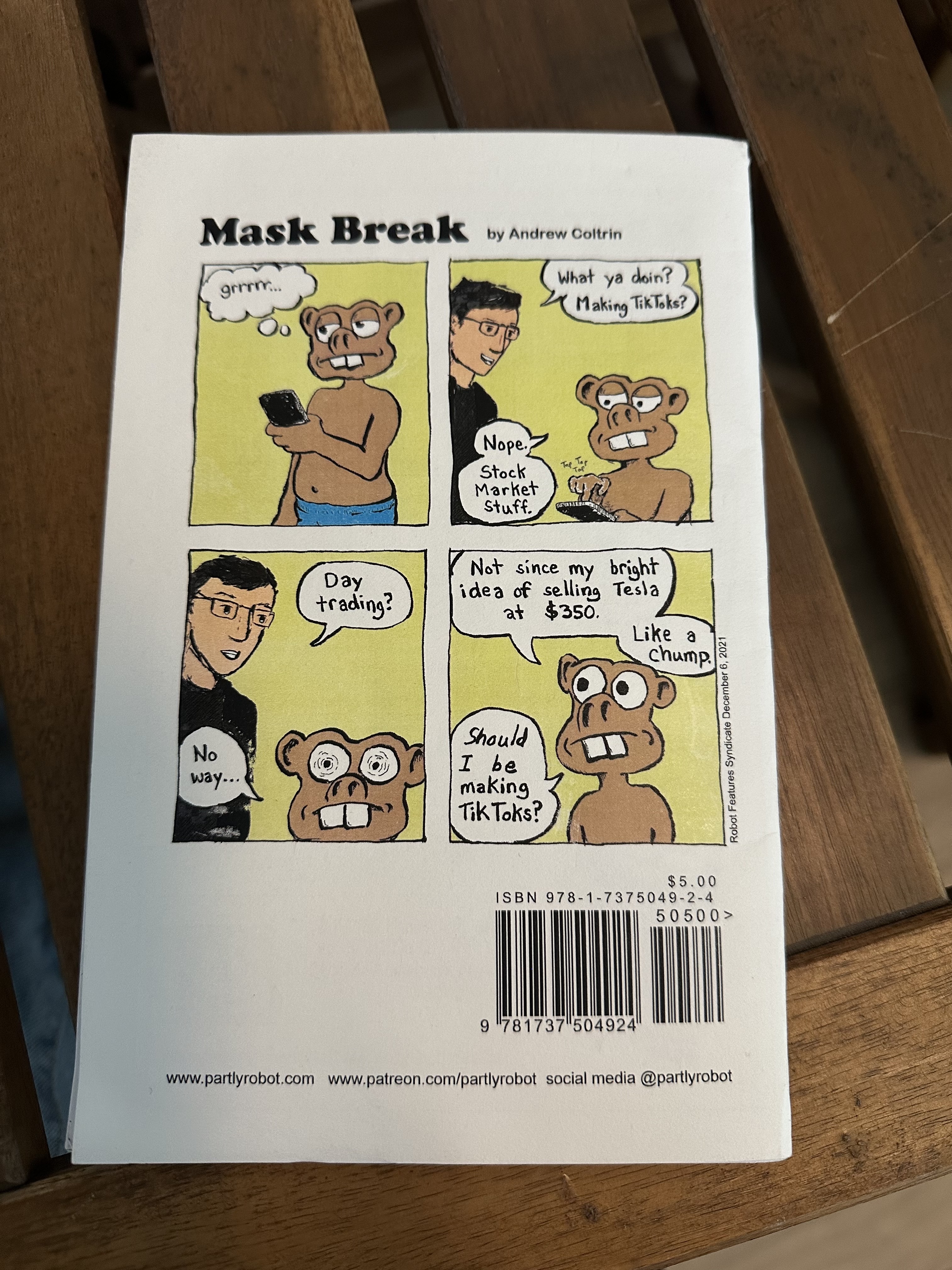

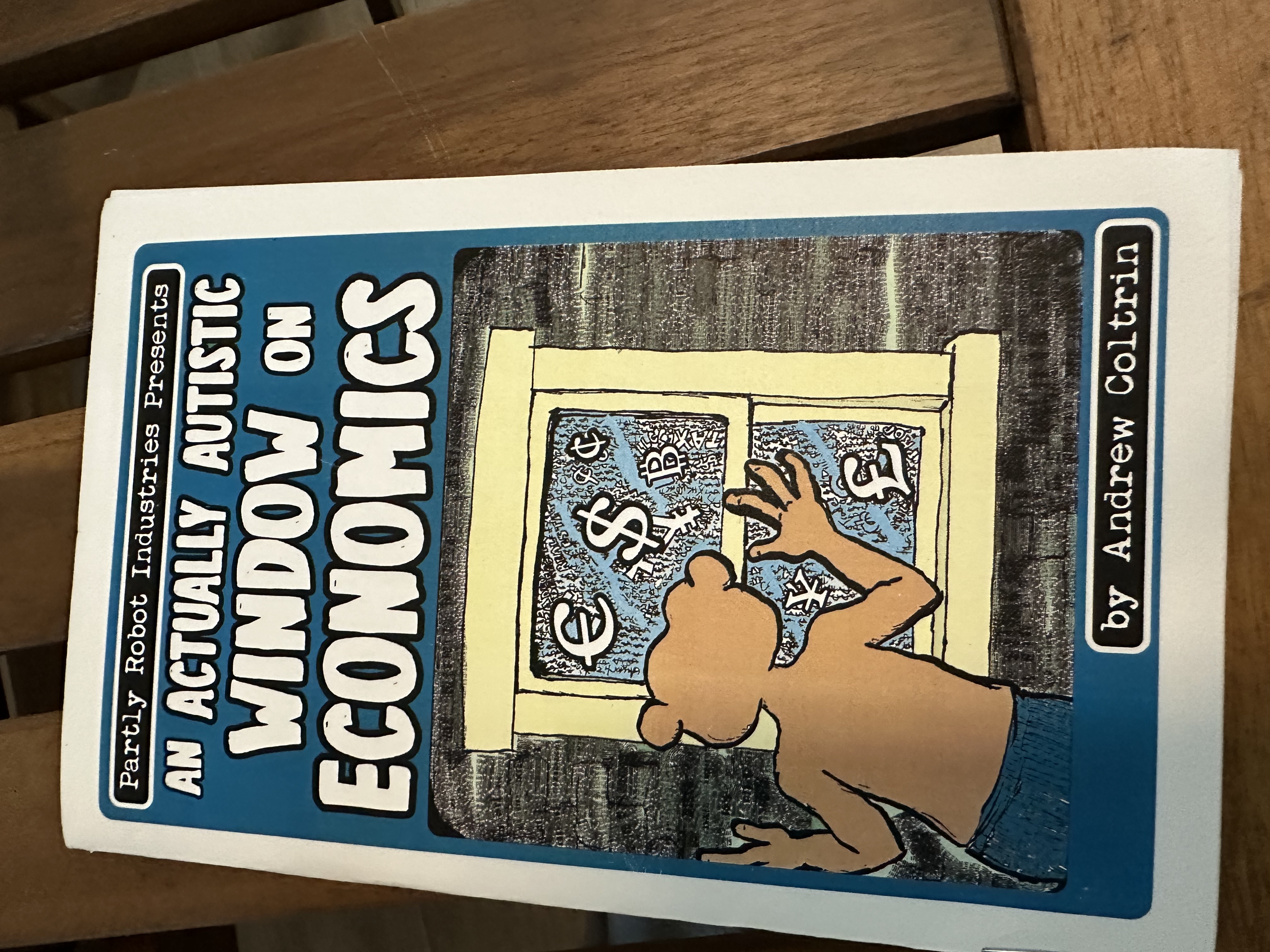

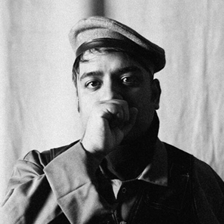

A couple of days after his talk about documenta, fried chicken, trauma and solidarity, we had the pleasure of listening to Hamja Ahsan speak about zines — in other words, listening to someone very knowledgeable speak about something he sincerely loves. Hamja had brought a suitcase full of zines to Amsterdam and spread them out on the downstairs table at Artistic Research Studio for guests to browse through at their leisure before he began.

DIY Cultures

Although he’s nowadays known for fried chicken and Shy Radicals, Hamja’s proudest achievement has been DIY Zine Cultures, a zine fair he co-initiated in 2013 and ran for five years together with Helena Wee and Sofia Niazi. Having attended and tabled at countless zine fairs over the years, Hamja confidently stated that DIY Zine Cultures was the greatest zine fair of all time. The second greatest, according to him, is Rotterdam Zine Camp.

What made DIY Cultures special, he explained, was a commitment to creating a community of all subjugated people, all people who have been treated unfairly, all people who are on the margins. It was to break out of the pattern of zine fairs as White hipster spaces, which he saw repeating everywhere from Brick Lane to Brooklyn. At the same time, DIY Cultures made space for shy, weird, disabled, unemployed, or otherwise marginalised zine makers regardless of ethnicity.

What are zines?

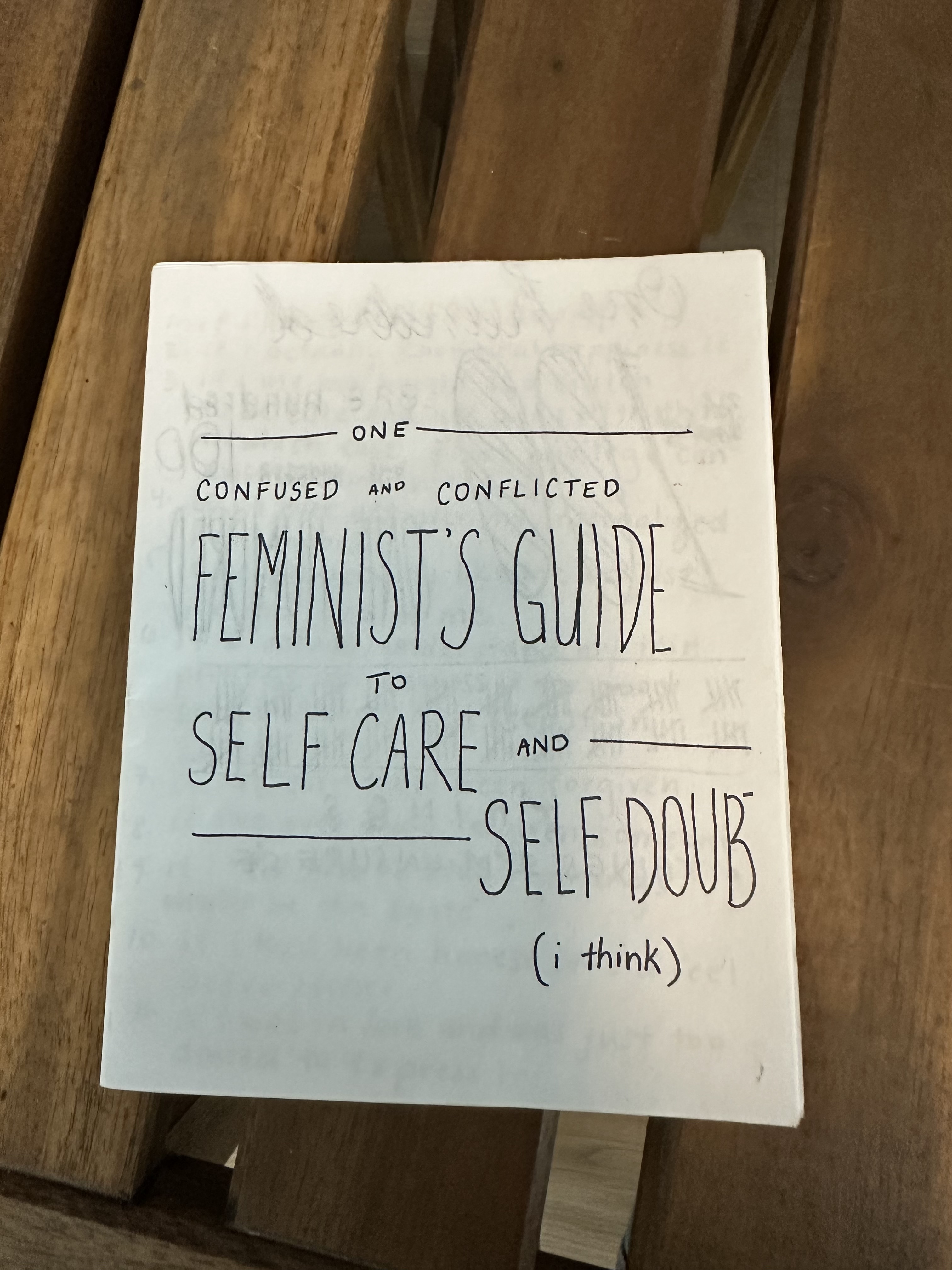

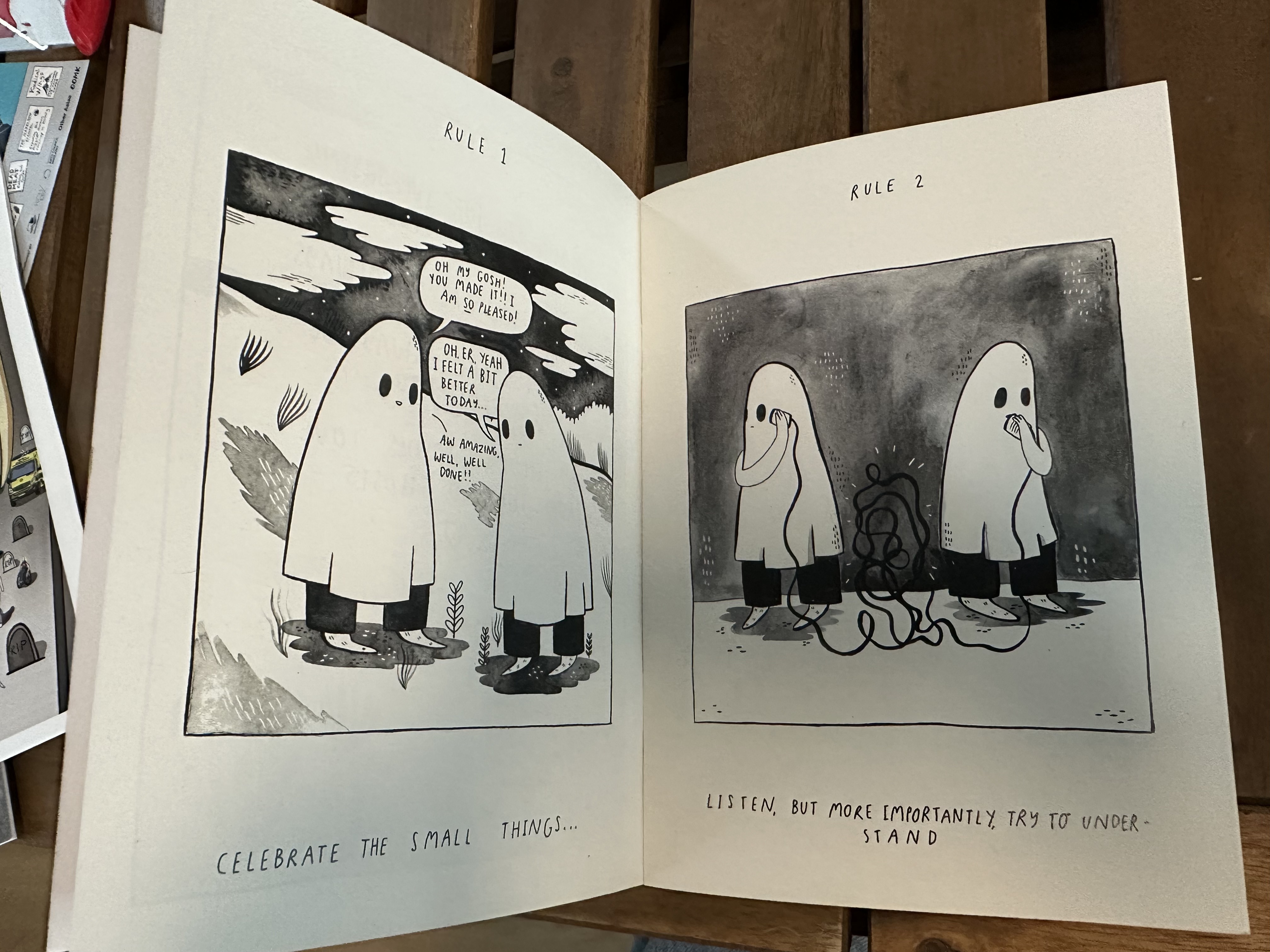

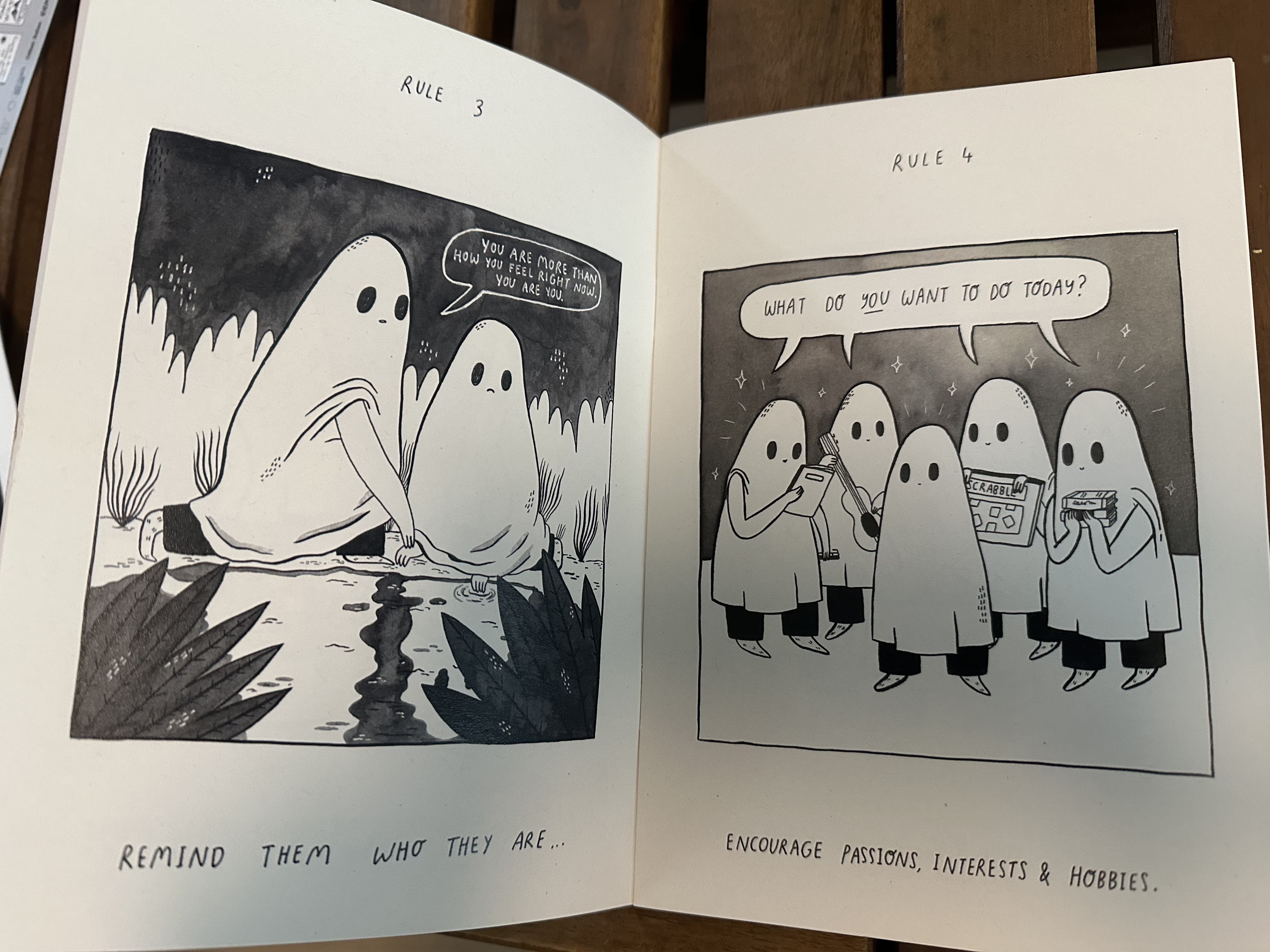

But back to the start. What is DIY? What are zines? They’re cheap, amateur-made publications with small circulation. But what do they represent? “To me, zines are an attitude”, Hamja said. “They're the antithesis of the mainstream, a resistance to bureaucracy, the over-bureaucratisation and over-professionalisation of life. I think the arts, certainly, have become over-professionalised, and also care, our approaches to politics, activism, lots of things.” He referred to the phrase “multicultural managerialism” coined by art theorist Sarah Marahaj. “All these forms of inclusion become too managerial. That’s why zines are important.”

Literary festivals, too, are professionalised and managerial: “You see Salman Rushdie for the hundredth time. Or Owen Jones, if you're a leftist. There’s a corporatisation and monopolisation of knowledge production in left spaces.” DIY Cultures countered this tendency. One of its most popular panels, for example, was on unemployment and creativity. The panel featured, among others, the Turkish comedian Saban Kazim, whose zine ‘Joke Center’ is unfolds on an actual unemployment form.

“I've spent a lot of time in unemployment or precarity”, Hamja explained. “And I developed insights and knowledges through that which, to me, is more valuable than hearing the same five famous speakers over and over.”

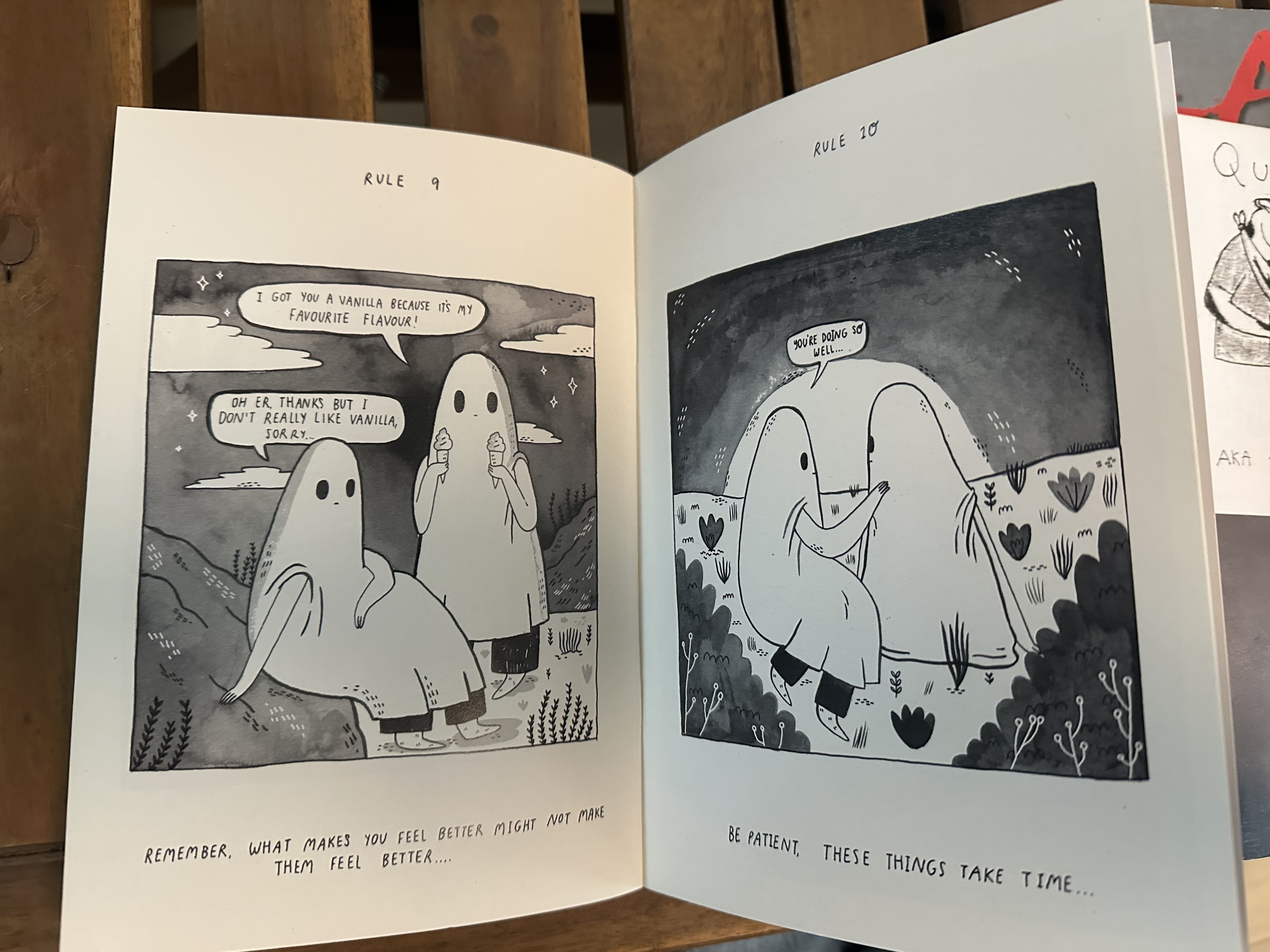

Zine cultures come with mutual support and conviviality. “I guess it's as if anarchist communities were actually good, and everyone mutually backed each other up. We're not dog-eats-dog, we’re not competing with each other, we’re not in different leagues. It's like this table with soup, right?”

We were sharing lentil soup that day and had moved Hamja’s neurodiversity zine collection to safety on the other half of the table.

Neurodiversity zines

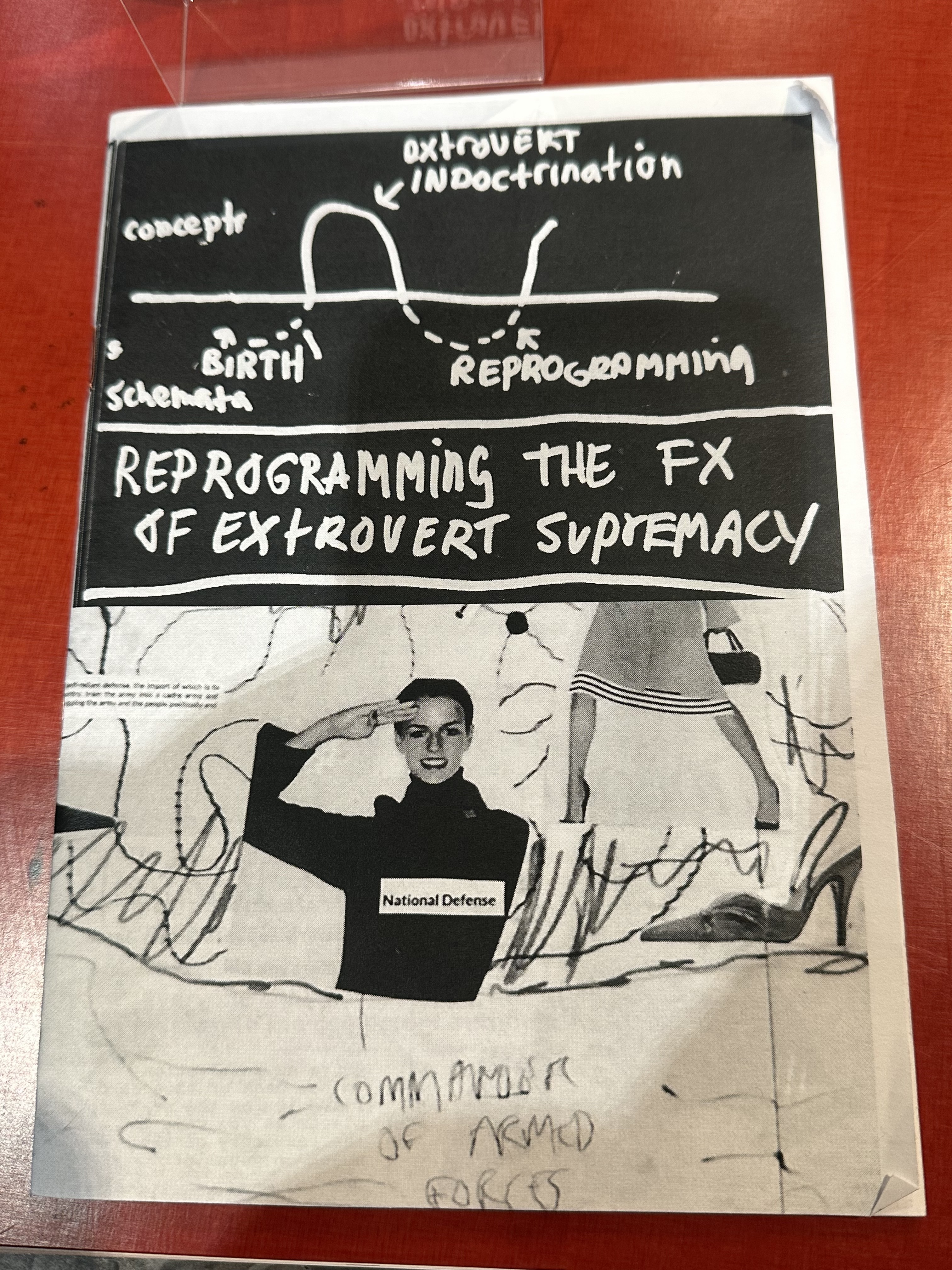

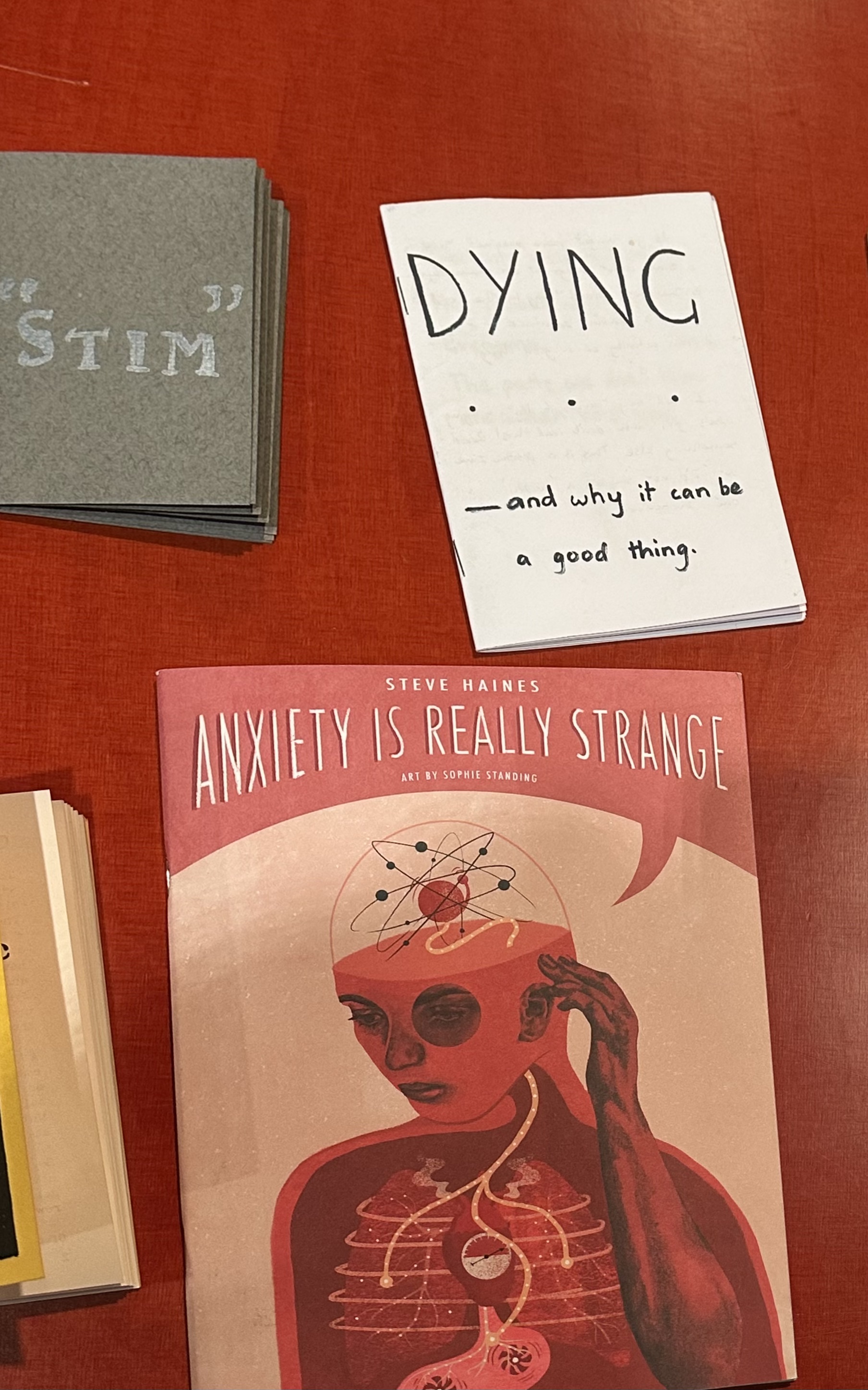

Zine cultures were how Hamja first engaged with neurodiversity. “Not through clinical definition, not through the medical system, or the welfare system”.

He showed us some examples from the disability zine collection of the Brown Zine Archives. “There’s a zine called F.U. I'm Dyslexic, and one about disability called Don't Fucking Look At Me, Thanks. It's very, very different language from a charity or an NGO, isn't it? Not too positive, or like a management speaker.” The zine ethos intersects with neurodiverse struggles and desires: “They don’t want to be mass marketed, so they appeal to that side of you that is unemployable, unmarketable, abject, unwanted.”

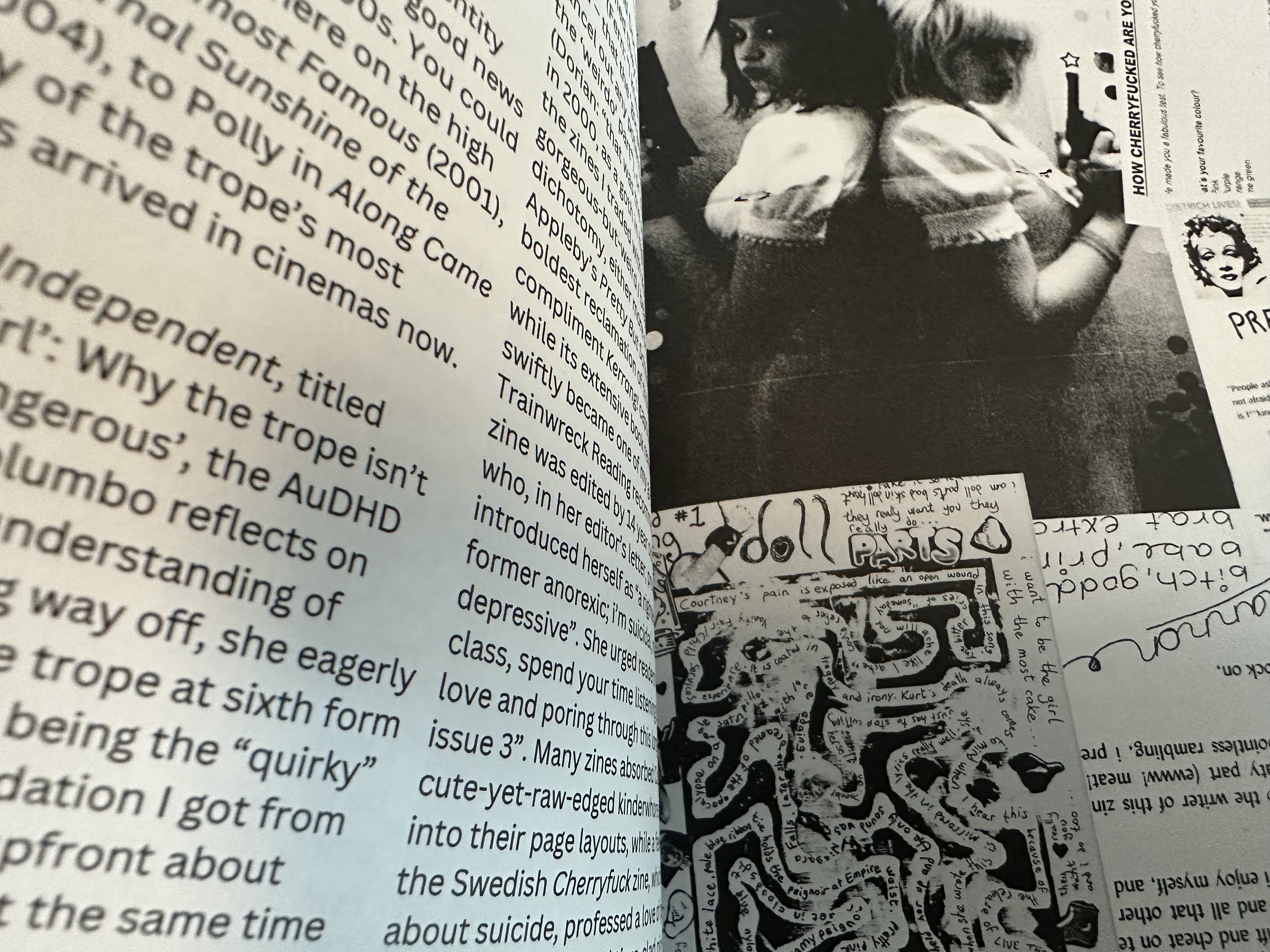

The past decades’ zine-renaissance also featured a wave of zines on the topic of neurodivergence, with zine communities forming around every diagnosis. Some of Hamja’s favourites: A is for Awkward by Rachel Rowan Olive, DSM 69 by self-described “professional madwoman” Dolly Sen, and the zines of the Icarus Project. The collection spread out in front of us, was remixed with zines on homelessness and austerity: “Those are also very much disability concerns.”

Zine origins

Hamja started making zines at age 13, in the early 1990s: “I wanted to change the world through my dad's photocopier.” His first zines were constructed with Microsoft Word and some scissors.

The impulse came from his immersion in London’s alternative, independent music scene through the newspaper NME and, a little later, sneaking into gigs.

One figure Hamja particularly identified with was Richie James Edwards of the Manic Street Preachers, who inspired dozens of fanzines at the time. In in-depth interviews, Edwards spoke about left-wing politics, eating disorder and mental health struggles while hospitalised for manic depression. He disappeared at age 27 and was later declared dead.

From fanzines and photocopiers, Hamja moved on to political zine making. He joined the collective Other Asias and made zines about Jinnah and the partition of India and Pakistan. “Even though it's British history, their biggest colony becoming independent, it was very rare to find a British person who knew who Jinnah was.”, Hamja said. Other Asias produced a zine-like artist newspaper called Redo Pakistan, exploring contested histories and futures of the region. While studying at Central Saint Martin’s, he wanted to connect with Bangladesh, the country his parents are from and where he holds dual citizenship, but was met with unsympathetic disinterest from his tutor. So once again, he turned to zine as a way of doing the work anyway.

In London, zine culture is preserved in the Stuart Hall Library zine collection. “I’ve actually lost some of the zines I made in the early 2000s”, Hamja said, “but there’s a copy in the Library.”

Rethinking access: One string and a coconut shell

Hamja not only collects zines, but also has encyclopaedic knowledge of cultural figures, initiatives and art practices matching the zine ethos, from pirate radio practices of Black urban communities in the UK to the Baul in Bangladesh, a group of traveling musicians: “They have this guitar that’s just one string and a coconut shell.”, he showed us. “To me, that's DIY culture.”

Zines represent communities beyond the mappable checkboxes of demographic categories, gender, and postal codes: “There's other things I relate to.”, Hamja said. “I relate to autistic people, awkward people, people who like” — he gestured at the table — “this type of soup. I relate to small spaces.”

How do zines and self-publishing make us rethink access?, he asked, also in light of the Radical Accessibility program he had curated the previous week for the Rietveld Academy’s studium generale.

Zines on the front lines

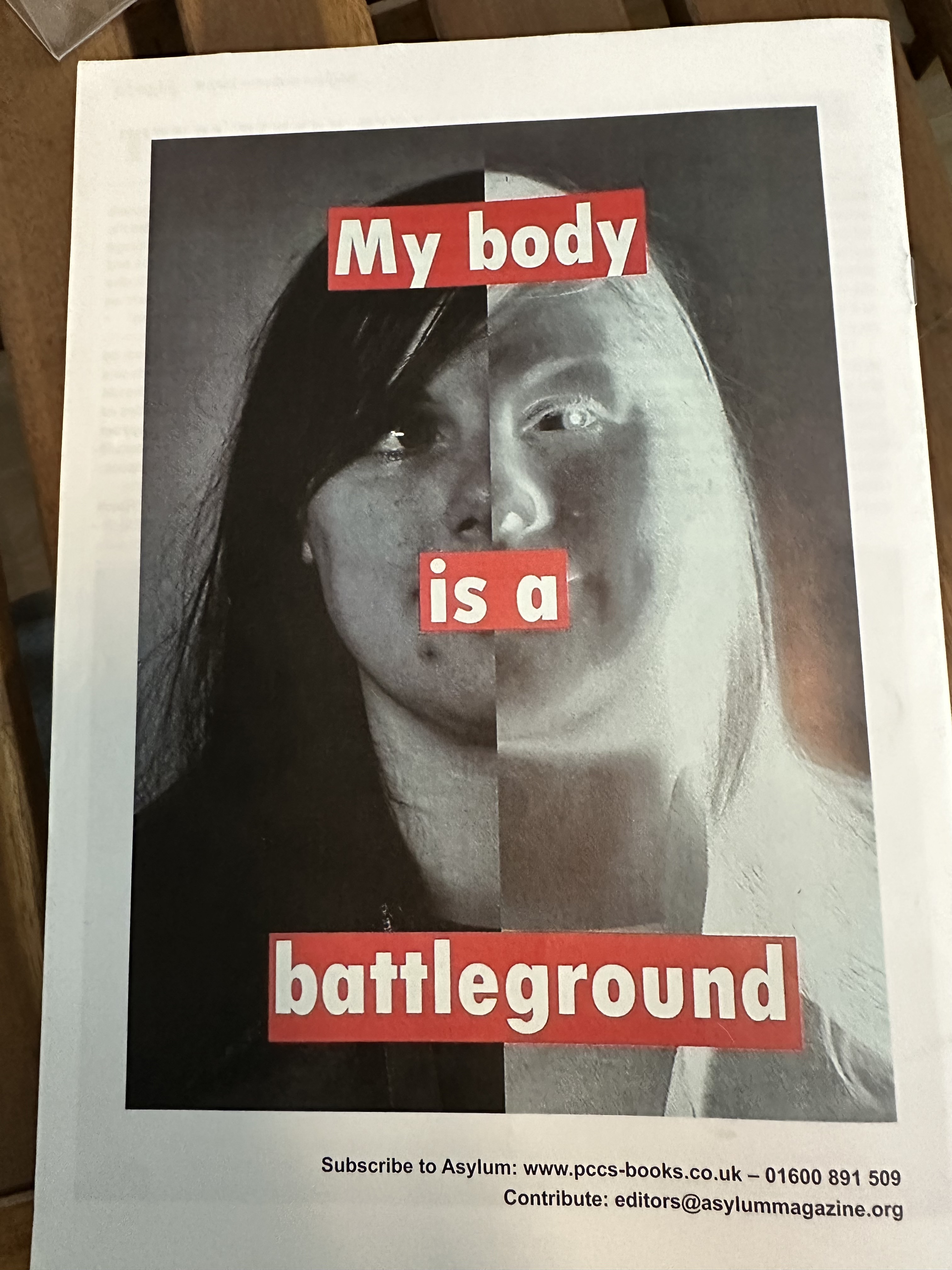

Zines tend to be made and spread in spaces that contest dominant power. Student encampment and teach-outs use zine libraries and rapid self-publishing as tools for protest. “I think lots of people there made zines without realising they made zines. Zine culture is not just resisting corporations. It's resisting state power, the excesses of the state.”

DIY Cultures also hosted workshops on the topic of resisting the British state program ‘Prevent’, which allows the state to monitor citizens from cradle to grave. “Even things like being shy and isolated in school is seen as terrorist suspicion. If you talk about Syria or Palestine, you could get your parents deported.”

Another unlikely frontier of zine culture are prisons. “Because my brother was in prison, I also have a huge collection of prison zines, a whole table like this.” There are zines written by people in solitary confinement for other people in solitary confinement: “Even at that level of total state repression, you need to keep your soul and your body alive. You can have the best lawyer in the world, but you need more than that. When a prisoner is free, they need community support. You need to feed them soup around the table, to reconnect. And that's what zine culture can do.”

Zines in the Netherlands

“The Netherlands are amazing for zine shops and artist books.”, Hamja said. From Page Not Found to Sans Seriffe and Perdu, Rotterdam Zine Fair and Mark Elberg’s Zine Depot in Arnhem, the Dutch zine ecosystem is alive and well.

Make zines, destroy fascism

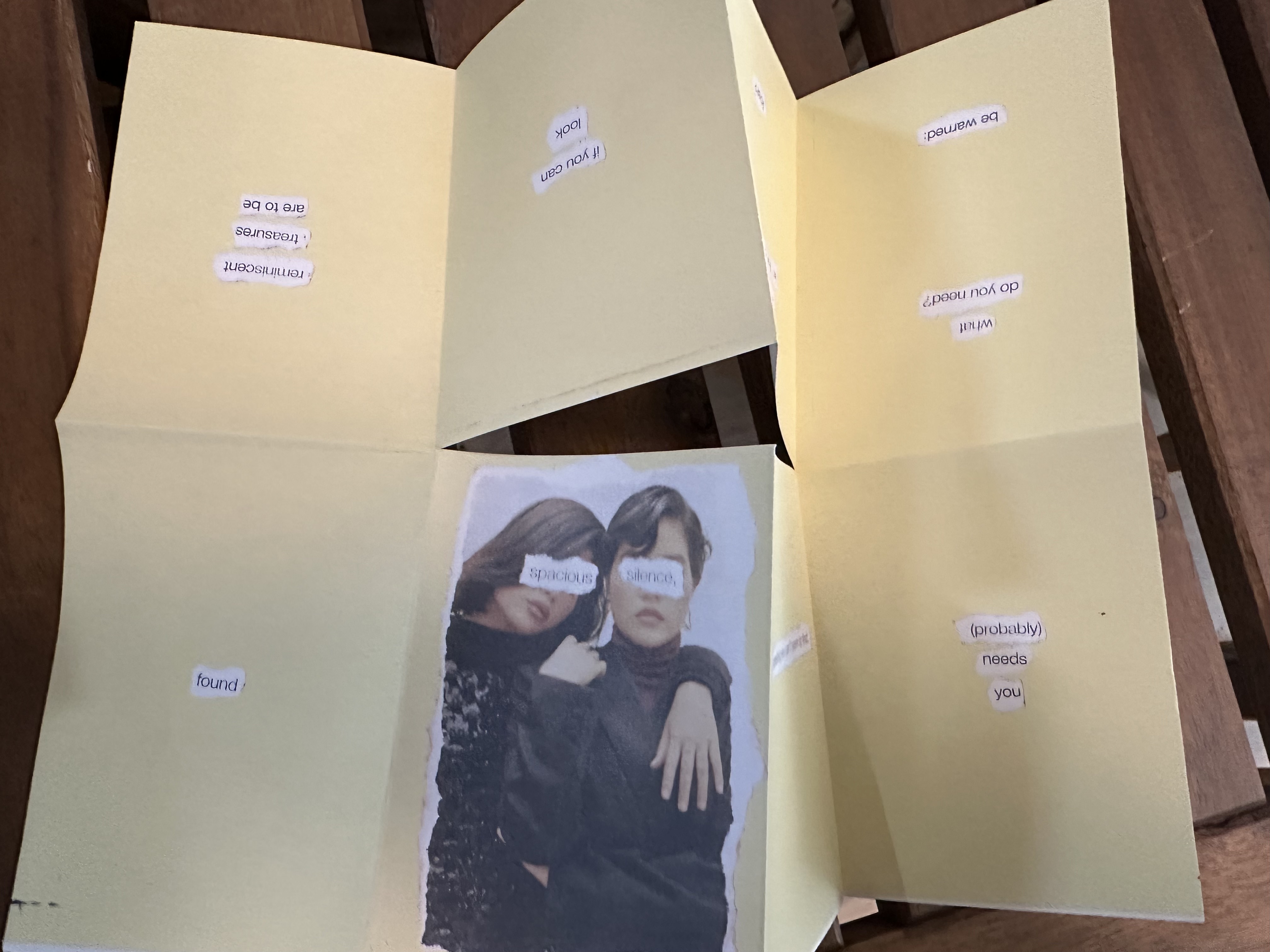

Hamja ended with a slide full of questions to ponder while working on our own 8-page zines made from one piece of A4 printer paper:

How does a zine differ from a mainstream publication? How does zine language differ from the brochure, the way we talk in the news, the glossy magazine, the way politicians, heads of departments, lawyers talk? What communities have been created with all these zines? What do you find interesting about a zine? How does it correspond with your practice and what you do? What makes a zine a zine?

His final message of the day:

“Make zines, destroy fascism.”

Follow on IG @shyradicals, donate on Hamja’s website, buy Shy Radicals.